INDIVIDUALS & PATIENTS

Taking control of your health journey starts here

With more than 2,000 locations and many at-home services available, we make it easier to access testing that keeps you and your family healthy.

With Labcorp OnDemand, you can purchase the same tests trusted by doctors, directly from Labcorp.

Get trusted, confidential results on everything from general health checks to specific areas like fertility, anemia, diabetes, allergies and more.

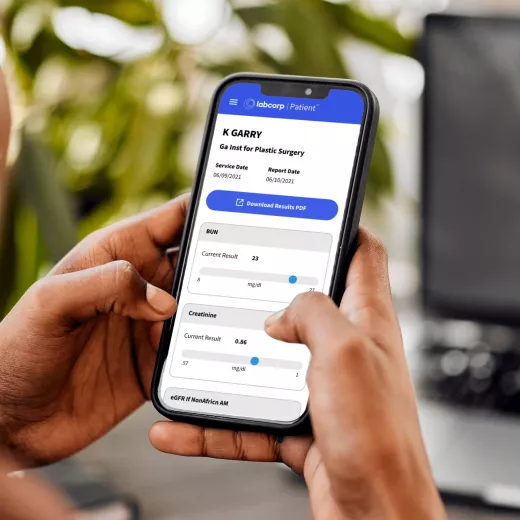

Our easy and secure Labcorp patient account allows you to get lab results, track your health history, manage appointments and pay bills—all in one place.

Get daily, personalized family health support and resources to guide you through every transition and important moment.